Agency

Feburary 18, 2025

I used to think that success was solely a result of willpower—that achieving your goals was just a matter of raw grit. But the reality is that willpower fluctuates. Some days, you feel like crap and just can't seem to give a damn about anything. Other days you are full of energy and motivation. It's unreliable.

Agency is different. It isn't just about resisting bad habits in the moment; it's about being in control of your life.

A year ago I could barely run a mile. This past Sunday, I ran my first marathon. The difference wasn't willpower—it was agency.

Agency vs. Willpower

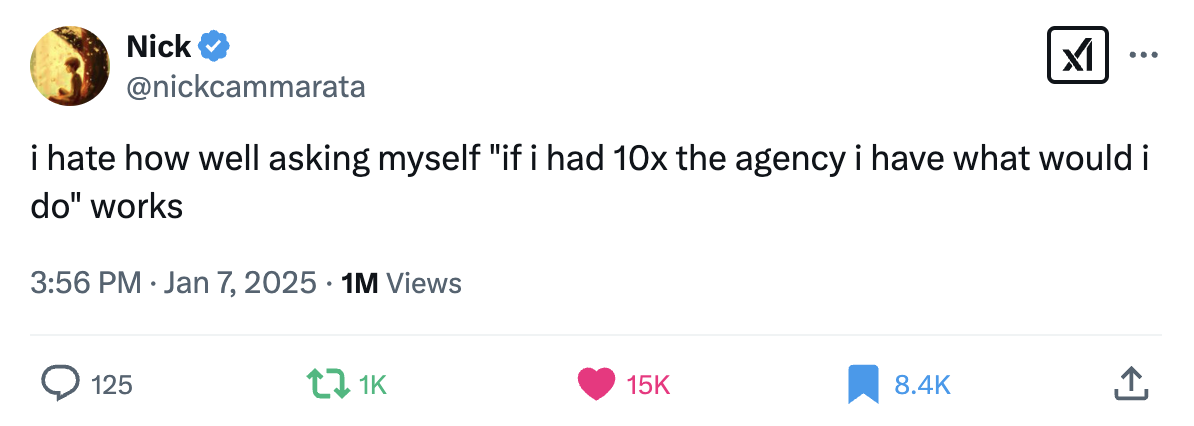

Recently, the above-pictured tweet blew up on the AI and tech side of twitter. Paul Graham found it so profound, he had this to say about it.

This may be the most inspiring sentence I've ever read. Which is interesting because it's not phrased in the way things meant to be inspiring usually are.

Upon first reading, it might sound like agency is just a synonym for willpower. There's a very important distinction. Willpower is your "mental strength," how much effort you can put into a task. You apply it on a micro level: reading through a boring part of a book or resisting eating junk food. Agency, on the other hand, operates on a macro level. It's the ability to act independently, to have control, to break the cycles of bad habits and to create new good ones.

Humans are inherently habitual. We tend to stick with familiar behaviors, even if they are ultimately making us unhappy. In the moment, we can use our willpower to stop a bad habit, like putting your phone down mid doom scroll. But to actually change your habits requires more than surface level self-control. It requires agency; structuring your life in such a way that makes achieving your goals as easy as possible.

Finding agency

A couple years ago, after graduating from college, I moved to Portland, Oregon, with my girlfriend. We packed up all of our stuff and drove over 1000 miles from Boulder, Colorado, to our new apartment in Portland. It was a radical shift. I went from living with dozens of friends, to living in a city I had never been to and knew no one.

Between social isolation, difficulties adapting to post-grad life, and Portland's gloomy weather, I quickly found myself in a rut. For the first time in my life, I felt deeply dissatisfied with myself. I was 30 pounds overweight, wasted much of my free time playing video games, barely read, and was making little effort outside of work to learn or advance my career. I knew I was wasn't living up to my potential, but I wasn't even sure what my potential was.

Things only started changing when, while stewing in my dissatisfaction, I asked myself a simple question: What version of myself would I look up to the most?

The answer jumped out at me, as if it had been there the whole time just waiting to be called upon. It was simple, but I had to admit it to myself: I wanted to be somebody who was hardworking, didn't waste time, woke up early, worked out, ate healthily, treated other people kindly, and was always learning and growing as a professional and a person.

To be fair, most people probably want to be something like this. The more important question was the next question I asked myself—one that reminded me of the tweet above: What would that person do every day?

The person I imagined was a version of myself with much greater agency. They would wake up early, exercise, work, study machine learning and do side-projects in their free time, and read every night. With the exception of work, I was doing none of these things.

There was only one remaining question: Why am I not doing those things? Why do I have it in my head that I can't do those things? I didn't have a good answer. That's when I realized that by not doing those things, I was choosing to be something other than what I wanted to be. To be the person I wanted to be required greater agency than I had been practicing.

Applying agency

Obviously, this revelation didn't fix all of my problems overnight—quitting bad habits, especially addicting ones like playing video games, is difficult and takes time. What it did do, however, was change the way I thought about my shortcomings. When I found myself falling into old patterns, I realized it wasn't due to lack of discipline, but lack of agency.

With this new perspective, I began experimenting with different ways to build agency into my daily life. After much trials and error, I've zeroed in on a small set of daily practices. Together, they form a system that gives me greater insight into my life, and thus, greater agency. Here are the three most important.

1. Habit tracking

Every day I track a small number of habits, such as exercising, reading, and my waking and bed time. This data is essential. Without it, you are always just a few days away from accidentally quitting a good habit. It forces you to be conscious of your own actions, thereby increasing your agency.

2. Writing

In today's age of overconsumption, it's rare that we give ourselves time to think. Writing offers that space. It allows you to articulate your thoughts and feelings in a way that can be hard to find elsewhere.

3. Defining a routine

One of the first things I implemented was a clearly defined routine, and it made an immediate difference. When you write down exactly when, where, and what you should be doing each day, you're much more likely to follow through. This doesn't mean scheduling every single minute of your day, but establishing a framework that keeps you on track.

Life now

It has been a long journey, but I've finally found a system that works for me. In less than two years, I've ran over 1000 miles, read dozens of books, and am generally much more satisfied in my life. Importantly, it doesn't take willpower for me to wake up everyday and run, or to read before bed, or to program for many hours a day. I do them all happily, but only because I made them part of my identity and my habits.

The Great Debate: Sutskever vs. Chollet on the Future of AGI

June 19, 2024

Are LLMs a Pathway to AGI?

Two of the most influential figures in AI fundamentally disagree on how we're going to achieve Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). Ilya Sutskever, former Chief Scientist of OpenAI and now Chief Scientist at Safe Superintelligence, thinks that if we keep scaling up LLMs, we'll eventually get there. On the other hand, François Chollet, creator of Keras, thinks that LLMs alone aren't enough.

Both Sutskever and Chollet have been on Dwarkesh Patel's podcast, where they've discussed their views on LLMs and AGI. It should be noted that Ilya's interview took place over a year ago, while François's interview occurred only a few days ago. So, it's possible that Ilya's views have changed in the past year. However, it's clear that Ilya is more bullish on LLMs than Chollet, so the majority (if not all) of his opinions probably still stand.

Sutskever's Interview

Early in the interview Dwarkesh asks Ilya, "What would it take to surpass human performance?" Right off the bat, Ilya challenges the claim that, "next-token prediction is not enough to surpass human performance." He argues against the premise that LLMs just learn to imitate, giving a straightforward counter argument.

If your base neural net is smart enough. You just ask it — What would a person with great insight, wisdom, and capability do? Maybe such a person doesn't exist, but there's a pretty good chance the neural net would be able to extrapolate how such a person would behave.

Ilya believes that LLMs are so good at generalization that they might even extrapolate the behavior of a "super" person that doesn't actually exist. Before ChatGPT was revealed to the world, almost nobody would have believed such a claim. But now, there seems to be a large number of people, both inside and outside the machine learning community, that believe LLMs can generalize well beyond their data. He goes on to discuss the implications of next-token prediction's success.

...what does it mean to predict the next token well enough? It's actually a deeper question than it seems. Predicting the next token well means that you understand the underlying reality that led to the creation of that token.

While Ilya doesn't explicitly define "understanding" in this context, it certainly sounds like he thinks LLMs are capable of much more more than just memorization. Ilya expands on the this idea:

It's not statistics. Like, it is statistics, but what is statistics? In order to understand those statistics, to compress them, you need to understand what is it about the world that creates this set of statistics?

Here, I believe Sutskever is arguing that the only way an LLM could be so good at predicting the next token is by actually compressing the data in a way that reflects the underlying reality of the world. Essentially, he's saying that while LLMs are just statistics, that doesn't actually mean that they have no understanding. In fact, Sutskever seems to think that the only way to be so proficient at next-token prediction is to have a deep understanding of the world.

I find this argument compelling, but I think it still an open question how much "understanding" is really going on versus how much memorization is involved.

Chollet's Interview

While Ilya only touches on LLMs relation to AGI in his interview, the majority of François Chollet's interview revolves around the topic. Within the first couple of minutes, Chollet explains how he believes LLMs function.

If you look at the way LLMs work is that they're basically this big interpretive memory. The way you scale up their capabilities is by trying to cram as much knowledge and patterns as possible into them.

While this statement doesn't directly contradict Ilya's claims, it's clear that Chollet is less impressed by LLMs ability to generalize. Later in the interview, he goes into more depth.

If you scale up your database, and you keep adding to it more knowledge, more program templates then sure it becomes more and more skillful. You can apply it to more and more tasks. But general intelligence is not task specific skills scaled up to many skills, because there is an infinite space of possible skills.

Now this directly contradicts Ilya's claim that LLMs can extrapolate the behavior of a "super" person. Chollet continues by explaining what general intelligence actually is.

General intelligence is the ability to approach any problem, any skill, and very quickly master it using very little data. This is what makes you able to face anything you might ever encounter. This is the definition of generality. Generality is not specificity scaled up. It is the ability to apply your mind to anything at all, to arbitrary things. This fundamentally requires the ability to adapt, to learn on the fly efficiently."

Chollet argues that general intelligence cannot be achieved merely by scaling up models or training data. He explains that more data increases a model's "skill" but does not bestow general intelligence. I love the way he succintly summarizes this: "Generality is not specificity scale up."

Throughout the podcast, Chollet carefully explains why he thinks LLMs lack understanding and are really just "memorizers." He goes so far as to say that LLMs lack intelligence altogether. Personally, I think this is very much dependent on your definiton of intelligence, but his point is well taken.

To aid in the search for general intelligence, Chollet created the ARC challenge, a test he believes can only be fairly completed by using general intelligence. He notes that an LLM or other model could be trained on many millions of ARC-like problems, and that it might be able to beat ARC, but that it would be "cheating" in a sense. He argues that the model would not actually be learning to generalize, but rather memorizing the answers to the ARC problems.

Interestingly, the state-of-the-art model on the ARC challenge does in fact use an LLM, but it adds quite a bit of extra machinery to the model to help it generalize. In the podcast, Chollet explains how he expects an LLM to be part of the final solution to AGI, but that it will need to be combined with other techniques to achieve general intelligence.

Conclusion

While Sutskever thinks AGI is mostly a matter of scaling up LLMs, Chollet is unconvinced. It's evident that even top AI researchers cannot agree on the correct path to AGI.

Estimates for achieving AGI vary widely, from a few years to several decades. Chollet even suggests that LLMs have slowed down progress towards AGI, stating, "OpenAI basically set back progress towards AGI by quite a few years, probably like 5-10 years." Only time will reveal whose perspective is closer to the truth.

If you haven't already, I highly recommend listening to both podcasts. Here's the link to Ilya's and here's a link to François's.